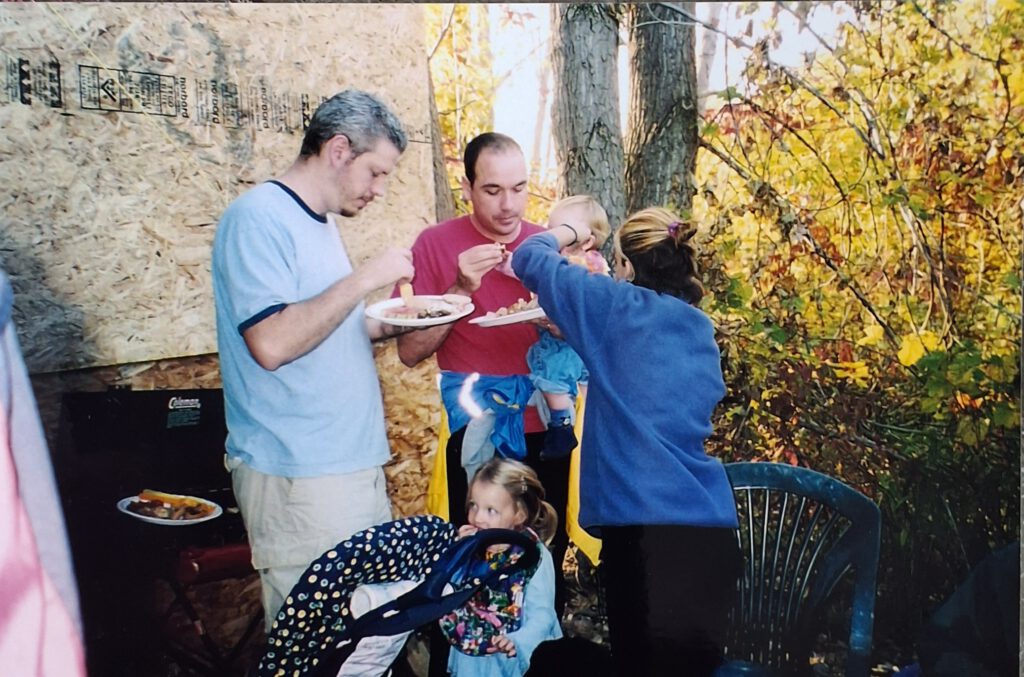

These pictures are from Thanksgiving day fest.

There was lots of food that people brought in to eat.

I have no idea how far, or where the few trees came from that where used to build the longhouse.

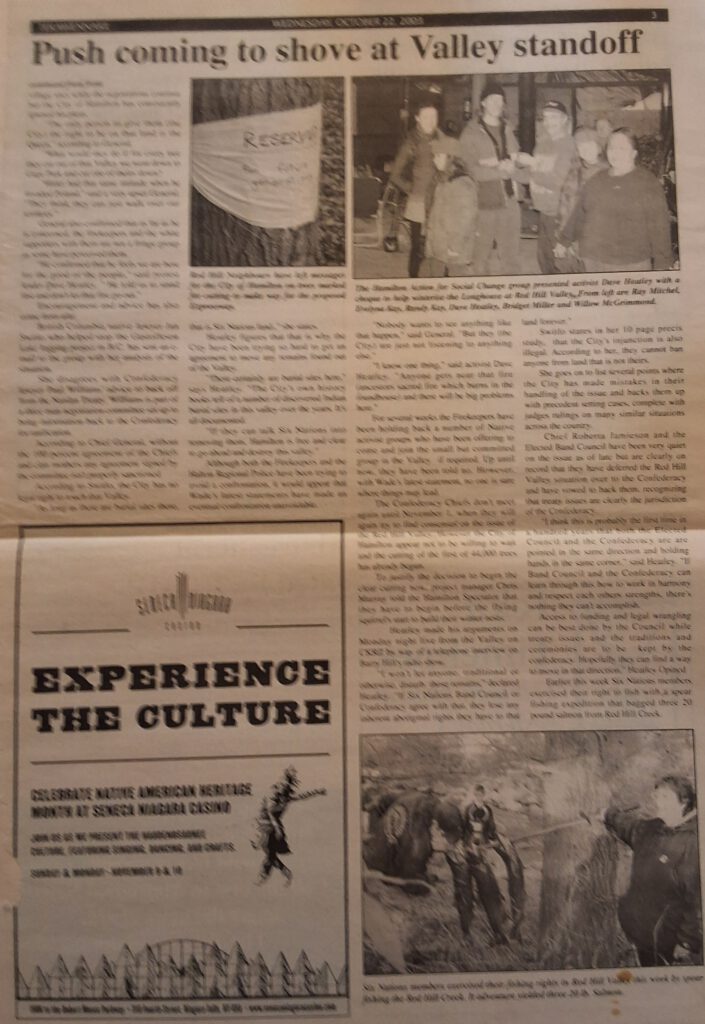

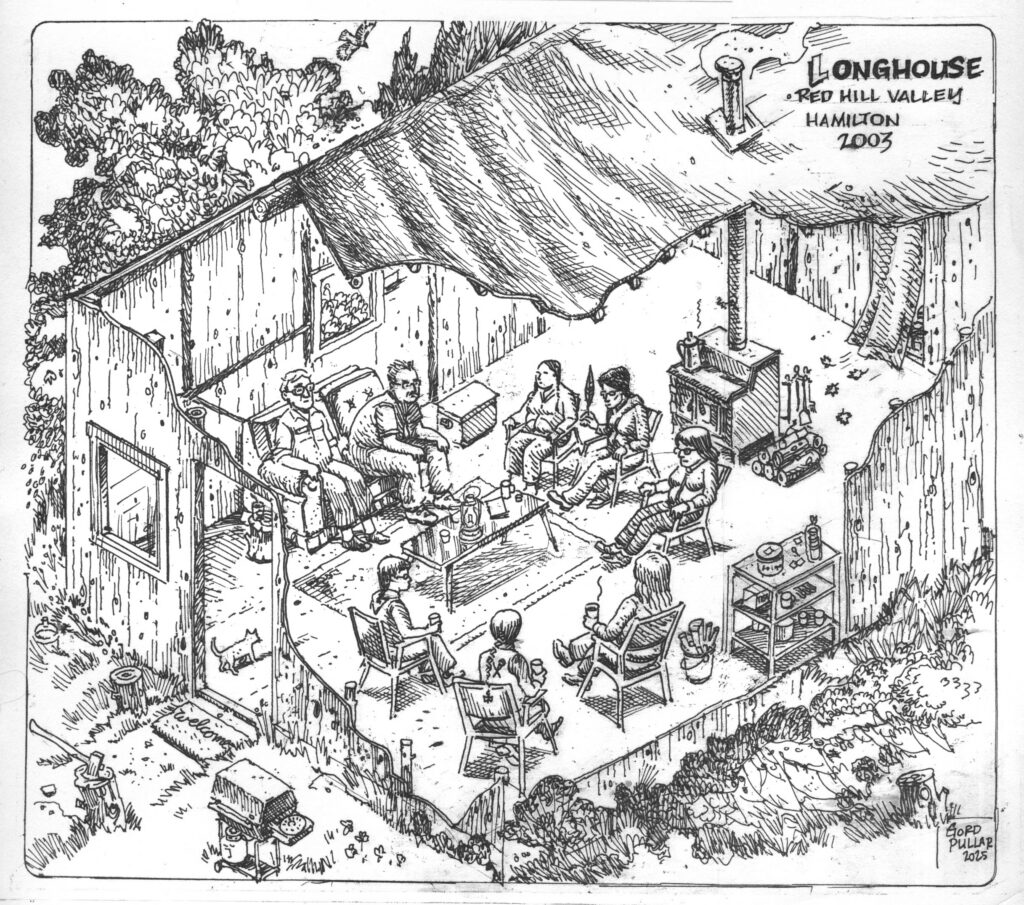

Before long, tarps began to appear, covering the roof of the Longhouse, and a wood stove was brought into the Valley. Within a few days, plywood was laid on the floor and walls, giving the structure a more solid form. A back door was added, along with an outdoor toilet dug into the brush behind it. I am not sure how many people eventually moved into the Longhouse. During this period, a lawyer visited the Valley to discuss strategies for laying claim to the land. It was an exciting time, though I was unable to witness some of these developments firsthand, as my work kept me away during certain key moments. Listening to the lawyers speak about our rights to the land felt like a crash course in treaties, land ownership, and the workings of government at every level.

At first, I was not sure I was ready for all of it. But I made the decision to learn everything I could about our treaties—and about the ways in which governments, time and again, treat First Nations people as though we do not belong anywhere.

As the days went on, my friend—the one who had been driving me everywhere—began writing to the CRTC to challenge the unfair and biased press coverage we so often received. One day, he arrived with a letter from the CRTC in hand and told me that I needed to handle it. At first, I thought he was joking, but he handed me the letter to read for myself. Unsure how to proceed, I called the Clan Mother for advice. She told me simply, “Handle it.” So, I contacted the senior editor at The Hamilton Spectator. His initial response was rude, but I pressed on. After hanging up the phone, I sat down and began writing letters—to every level of government, to the editors of the newspaper at the time, and to the CRTC.

Barely half an hour later, the same person who had been so rude toward me called back to say they would come into the Valley to meet with us. I asked that the meeting take place after my workday ended at 2:30 p.m. I immediately called my friend, the Clan Mother, and she gathered a group of women to be present.

In the Longhouse, we had an old couch and several chairs. The women arranged the chairs in a half-circle facing the couch, ready for the conversation to come. The men from The Spectator arrived on time, unaware of what they were about to face. We spoke directly with the editor-in-chief, explaining how the coverage of the protest had harmed us as Native women. We urged them to review their past reporting and to consider the impact their words and images had on our community. I was not sure if our message had truly reached them.

But a few days later, I was walking toward the Roundhouse when I saw the reporter who regularly visited to take photographs and write about the protest. He was ahead of me, speaking to someone and explaining that he had just met the woman responsible for making The Spectator change how it told our story. Hearing that was deeply satisfying—it felt like the beginning of real change. Following our success in engaging The Spectator, I called CHCH to arrange a meeting with their senior staff, bringing along my friend, the Clan Mother, and a small group of women. A Native woman working at CHCH learned of the meeting through a friend and asked to attend, and we welcomed her. We were tired of the negative press and personal attacks. CHCH, however, was different from The Spectator. Their team was not dismissive; they listened respectfully to the Six Nations people who came to speak. Only one reporter joined the meeting that day, and he explained that they needed interviews. We told them we could not provide those, as any public statements had to come from the Confederacy Chiefs and Clan Mothers. Non-Indigenous allies could speak, but the media was not interested in them—they wanted interviews with us. I could not speak on behalf of the community, as I was not from there and had no authority in many matters.

The Clan Mothers would often tell me, “You are a strong woman and unafraid to speak out for what is right.” My response was always the same: “If you want change, you need to speak up for real change.” My understanding was that Clan Mothers are the heads of their clans and have the right to guide their people, yet too often it seemed the Chiefs were operating under the old colonial model, holding the decision-making power.

News soon came from the Onondaga Confederacy Longhouse that the City would be allowed to dismantle the Roundhouse and Longhouse. Nothing happened immediately, but the Chief who had helped initiate the movement was back in the hospital. Once again, he asked me to stay and help the Clan Mother, knowing she would need someone to protect her. By then, the people were preparing to split into different groups and set up camps elsewhere in the Valley—a division that played directly into what the police wanted.

Many seemed relieved to leave the Longhouse. The women held a meeting with one of the men who had opposed us from the start. He was upset when we told him he could not attend, as the matter did not concern him—until we later discovered that he had been the one advocating for AIM to take over the Valley.

Inevitably, I was blamed for many things, with some claiming the Clan Mothers “knew nothing.” My friend, the Clan Mother, set the record straight, insisting that people stop underestimating the women and treating them as relics of the past. We did not see that splinter group again until we heard they had been arrested at their new campsite. I arrived at the sacred fire later that day and asked the fire keeper what had happened. He said it had been quiet until those arrested returned. One man waved his ticket in the air, declaring they should challenge the police. When I asked who he was and what was going on, everyone fell silent and moved to the Longhouse. Later, a woman explained to me that the police had arrived early in the morning, before they were even awake, and had taken them to jail for the day. Once they returned, the tension faded, and the Valley was calm again.

That evening, I called the Clan Mother to let her know everyone was back, though the mood had shifted—we were unsure who to trust, especially as we were being blamed for the raid at the second camp. That was when the Six Nations Chiefs appeared to wash their hands of the protest. The Chief who had been with us died soon after. We received word that the police were preparing to enter the Valley to shut it down. I was at work when it happened and did not witness the arrests or the destruction of the Longhouse and surrounding trees.

The police allowed us, as Native women, to enter the Valley one last time to tend the sacred fire. There was a large crowd outside the fence the City erected after the arrests, many of them crying and offering hugs as we passed. Inside, we placed tobacco on the last of the fire, thanking the Creator for keeping us safe and expressing sorrow that we could not do more.

My friend still wanted to proceed with legal action, so we met with the lawyer, who offered examples of cases we might use. But her health declined again, forcing her to step back. We turned instead to enjoying time together—attending a New Year’s Eve party dressed in our best, taking a trip to Toronto with the schoolchildren where I worked, and participating in Six Nations meetings on women’s roles in their society. Through these gatherings, I came to know more of the women from Six Nations and reconnected with people from the Valley. We visited each other’s restaurants, shared meals, and spent time with my friend’s mother—a woman of immense strength and grace—who generously shared her people’s history. Listening to her, I recognized the same struggles faced on my own reserve and others across the country. I enjoyed listening to her stories and realizing that, in many ways, their lives were much like others. We had no real voice in decision-making, and that absence of representation strengthened my resolve to keep struggling for peace and to be fully part of society.

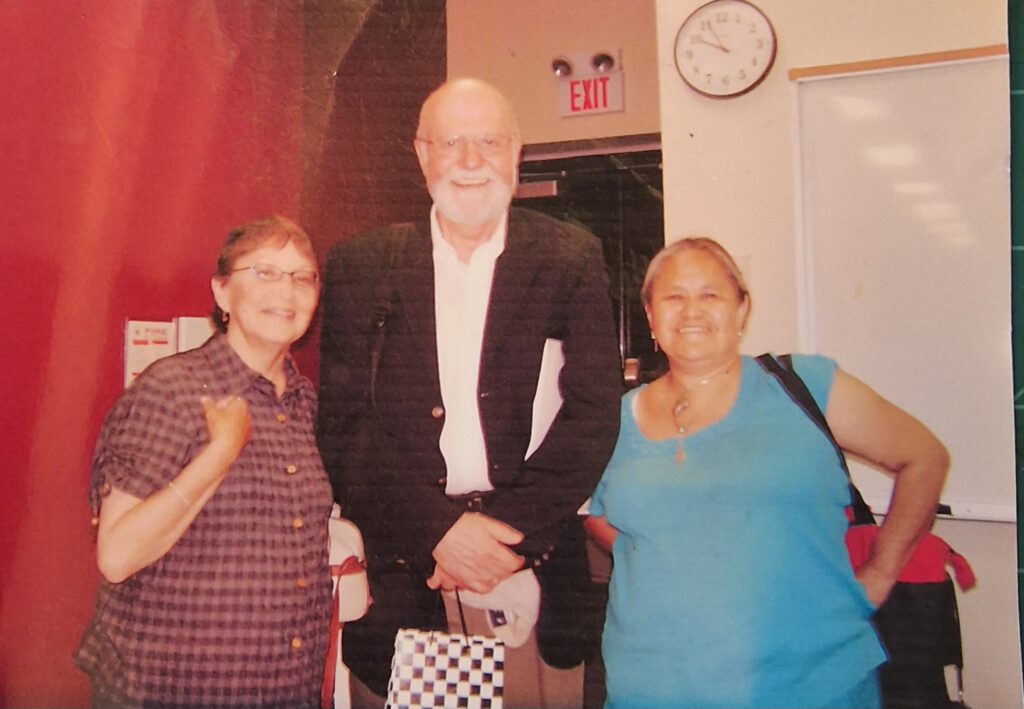

It was around that time that I met Jack Layton. Everyone kept telling me I needed to meet him. On the day he came to Hamilton, I was at work. A friend picked me up afterward to go home for a couple of hours before the meeting. I could not remember his name at first—I told my friend it seemed important for me to meet “this guy.” She asked who I meant, and I replied, “I think he has something to do with the NDP.” She laughed, already knowing exactly who it was. When I finally met Jack Layton, I asked him directly what he would do for First Nations people. He told me to read his website for information about his policies. I pressed further, asking if he knew what was written there. He admitted that he did not. I left the conversation feeling deeply disappointed. I repeated my question about his policy and how he intended to help, but again he referred me to his website. I explained that I had never read his—or anyone’s—website before and had never thought to do so. A friend took a photo of me with Jack Layton, and shortly afterward, he was surrounded by First Nations people.

0 Comments