August 3, 2003

The Red Hill Valley Protest began with a rally at the Green Hill site on a Sunday afternoon. I had just returned from visiting family in British Columbia and was looking forward to some quiet time. I called my son to pick me up, but he was not home. I reached out to several friends, but everyone seemed busy. Finally, I called my neighbor, and she graciously came to pick me up from the bus depot.

Not only did she welcome me home, but she also invited me to join the rally in the valley. I agreed, as I was still on holiday, and felt it was a good opportunity to learn more about the situation. I spent the day listening to the speeches and discussions. The media took photographs of some of the participants, and I ended up in a picture, directed by someone who guided me to a spot. At the time, I did not fully grasp the significance of being there.

We decided to walk around the Valley and as we did, memories and visions came rushing back to me. It was a profound experience—one that left me torn between staying or running away. We hiked for about an hour, soaking in the atmosphere, before deciding to return the following day.

Upon our return the following day, we stayed for about four hours. I was asked to stay because the permit required the presence of a First Nation person to remain valid. One of the Confederacy chiefs had signed the permit, believing strongly in the need to protect the valley—the last green space in lower Hamilton. This valley was a cherished place, used by everyone for walking, fishing, socializing, and as a safe hangout for the youth.

It was here that I met the chief, who had just come out of the hospital. He was one of the creator’s warriors. He was a kind and humble man, and though I did not speak much with people there, I quickly began to learn from those around me about the valley’s deep cultural and spiritual significance.

We stayed out on the street for a couple of weeks and as my involvement deepened, I was invited to the Onondaga longhouse at Six Nations. I was unfamiliar with their customs and rules. Though The Clan Mother who had been with us on the picket line, could not be there on that day, she gave me guidance on how to handle myself there, which was quite helpful- although I was still nervous about talking to the people there.

During my time at the Green Hill site, I had the privilege of meeting many remarkable individuals. I also noticed other Indigenous women present, though they were gathered on the opposite side of the site. At the time, I was unaware that there were two separate protest lines leading into the Valley—something I might have learned sooner had I asked more questions. Conversations with participants revealed that the struggle over this land had been ongoing for more than 50 years.

I carried my camera with me on most days at the protest lines, though in the early days I took few photographs. Much of the time was spent attending a variety of meetings involving different groups and voices from across the movement.

As my days at the site ended—I had to return to work—word came of a gathering to be held that weekend at the Onondaga Confederacy Longhouse. By then, I had met the Indigenous women from the other protest line, and the connections we forged became an important part of my experience in the Valley.

I was invited to attend what would become a profound and unforgettable experience—my first time entering another Nation’s house to seek their support in protecting the Valley from destruction.

We paused midday for lunch, and during that time the Clan Mothers began asking me questions about my Nation and about myself. I shared with them the dreams and visions I had for the Valley—visions rooted in respect, preservation, and the spirit of the land. In response, the Clan Mothers expressed their support, saying that a sacred fire could be established in the Valley.

The individual who had accompanied me was unfamiliar with the significance of the gathering. The Chiefs did not speak with him, and it became clear that this journey was meant for me to carry forward. I turned to him and said, “They’re sending people into the Valley to build a sacred fire.” The moment the words left my mouth, his excitement was so great that he nearly drove off the road upon hearing the news.

The next day at work, a colleague burst into my office with urgency in his voice, telling me that “the Indians were moving into the Valley with some kind of fire.” I smiled and explained that it was a sacred fire—an important spiritual and cultural tradition—being brought into the Valley. I couldn’t help but laugh quietly, as I had already known of the plan to light it at the crack of dawn.

I took the opportunity to share some of the history that is not often taught in schools, offering context about the meaning and significance behind what was taking place. It made for a long day, as I worked until 2:30 p.m. before finally catching the bus to the Green Hill site. From there, I walked into the Valley to witness the sacred fire and the people who had come to carry it.

There was an unmistakable sense of excitement around the sacred fire—energy and anticipation radiating from everyone gathered there. I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect from the people in the Valley, but the atmosphere was welcoming and positive.

Members of the media were present, capturing photographs of the event. I made a point of stepping into view, ensuring I was included. At first, I never saw any of my pictures appear in the newspaper or on CHCH News. But in the weeks that followed, I began to notice myself featured—identified simply as a protester—both in print and on television.

At the time, I was working in a middle school when my principal asked me to visit classrooms and explain why I was spending time in the Valley each day. The children regarded me with curiosity and respect, seeing me as someone with a story worth hearing. It was a privilege to speak with them about real history—history not always found in their textbooks.

While most mainstream media coverage cast the protest in a negative light, there were exceptions. Two Indigenous newspapers and CBC Radio reported our story with fairness and depth.

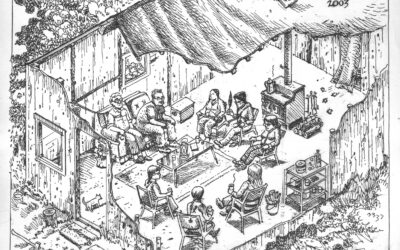

All of the NDP members came, and I even met one of our former mayors, who was then working as a radio news announcer. Life inside the Valley was very different from the picket lines. People arrived and departed at all hours, and I found myself learning about the lives, beliefs, and traditions of the Six Nations people, including the customs and protocols of the Longhouse.

0 Comments